Arthritis encompasses a wide range of joint-related conditions, all of which involve inflammation in the joints, leading to pain, stiffness, and reduced mobility. Among the many types of arthritis, osteoarthritis (OA) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) are the most prevalent, each affecting millions of people worldwide. While both conditions share the common characteristic of joint pain, they differ significantly in their underlying causes, symptoms, and treatment approaches.

Osteoarthritis is primarily degenerative, often called “wear and tear” arthritis. It develops gradually over time as the cartilage that cushions the joints wears away, leading to pain and stiffness, particularly in weight-bearing joints such as the knees, hips, and spine. On the other hand, rheumatoid arthritis is an autoimmune disorder in which the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks the joint linings, causing inflammation, swelling, and potential damage to other organs and tissues beyond the joints.

Understanding the differences between osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis is crucial for effective diagnosis and treatment. These distinctions are important for those living with these conditions and their families, caregivers, and healthcare providers.

What is Arthritis?

Arthritis is an umbrella term that describes a group of more than 200 conditions affecting the joints and surrounding tissues. These conditions can cause various symptoms, most commonly joint pain, inflammation, and stiffness, which can vary in severity and impact daily activities. The term “arthritis” means “inflammation of the joint,” but the underlying causes and effects of this inflammation can differ significantly from one type of arthritis to another.

The two most prevalent types of arthritis are osteoarthritis (OA) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA), each representing distinct pathways to joint damage and discomfort. Osteoarthritis is the most common form, primarily associated with degenerating joint cartilage due to ageing, repetitive stress, or previous injury. This leads to the classic symptoms of joint pain, swelling, and stiffness, particularly after periods of activity.

Rheumatoid arthritis, in contrast, is an autoimmune condition in which the body’s immune system mistakenly targets the joint lining. This leads to chronic inflammation that can cause joint damage, deformity, and even damage to other organs in the body. Unlike osteoarthritis, which develops gradually over time, rheumatoid arthritis can onset more quickly and affect multiple joints simultaneously.

Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common form of arthritis, affecting millions of people worldwide. It is a degenerative joint disease characterised by the gradual breakdown of cartilage, the smooth tissue covering the ends of bones where they form a joint. As this cartilage wears down over time, the underlying bones rub against each other, leading to pain, swelling, and decreased mobility. The progression of OA can also lead to changes in the bone itself, including the formation of bone spurs and the gradual deformation of the joint.

Osteoarthritis is primarily a result of mechanical wear and tear on the joints. It typically develops with age as the cumulative effects of years of joint use take their toll. However, several other factors can increase the risk of developing OA. These include obesity, which places additional stress on weight-bearing joints such as the knees and hips; previous joint injuries, which can accelerate cartilage breakdown; and genetic predispositions, which may make some individuals more susceptible to the disease. While OA can occur in any joint, it most commonly affects those that bear the most weight or are subjected to repetitive motion, such as the knees, hips, hands, and spine.

-

Symptoms and Progression

The symptoms of osteoarthritis typically develop slowly and worsen over time. The most common symptoms include joint pain, stiffness, and reduced flexibility. These symptoms are often most noticeable after periods of inactivity, such as first thing in the morning or after sitting for a long time. Still, they tend to improve with gentle movement. Conversely, prolonged or intense physical activity can exacerbate pain and stiffness later in the day.

As osteoarthritis progresses, the affected joints may become increasingly stiff and painful, limiting the range of motion and making daily activities more difficult. Unlike some other forms of arthritis, osteoarthritis tends to affect joints asymmetrically, meaning that one side of the body may be more affected than the other. The knees, hips, hands, and lower spine are the most commonly impacted areas, with the symptoms often varying depending on the joint involved.

-

Diagnosis and Treatment

Diagnosing osteoarthritis typically involves a combination of physical examination, patient history, and imaging tests. During a physical exam, a healthcare professional will assess the affected joints for signs of tenderness, swelling, and reduced range of motion. They may also review the patient’s medical history to identify any risk factors, such as previous injuries or a family history of arthritis. Imaging tests, such as X-rays or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), are often used to confirm the diagnosis by visualising the extent of cartilage loss and any changes to the underlying bone.

Treatment for osteoarthritis focuses on managing symptoms and improving joint function. While there is currently no cure for OA, a range of treatment options can help alleviate pain and maintain mobility. Pain management is often achieved through a combination of over-the-counter pain relievers, such as paracetamol or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and physical therapy, which can help strengthen the muscles around the joint and improve flexibility. Lifestyle changes, such as weight management and regular exercise, are also crucial in reducing the strain on affected joints and slowing disease progression.

In more severe cases, where pain and disability significantly impact quality of life, surgical interventions may be considered. Options such as joint replacement surgery can provide significant relief, particularly in the knees and hips, by replacing the damaged joint with an artificial one. Other surgical procedures, like joint realignment or cartilage repair, may also be recommended depending on the extent and location of the damage.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic autoimmune disorder that primarily affects the joints, leading to inflammation, pain, and eventual joint damage. Unlike osteoarthritis, which is caused by joint wear and tear, RA occurs when the immune system mistakenly identifies the body’s own tissues, particularly the synovium (the lining of the joints), as foreign invaders. This autoimmune response results in persistent inflammation, which can damage the joints and other parts of the body over time.

The exact causes of rheumatoid arthritis are not fully understood, but it is believed to involve a combination of genetic and environmental factors. A genetic predisposition can increase the likelihood of developing RA, particularly in individuals who carry specific genes associated with the immune system. Environmental triggers, such as smoking, infections, or exposure to certain chemicals, may also play a role in initiating the autoimmune response in susceptible individuals. Notably, rheumatoid arthritis tends to affect women more often than men, with women being up to three times more likely to develop the condition. Hormonal factors are thought to contribute to this gender disparity.

-

Symptoms and Systemic Effects

Rheumatoid arthritis is characterised by a range of symptoms that can vary in severity and may come and go over time. The hallmark symptoms include joint pain, swelling, and stiffness, particularly in the morning or after periods of inactivity. This morning stiffness is often prolonged, lasting for an hour or more, and can be a distinguishing feature of RA compared to other types of arthritis. The affected joints are typically those of the hands, wrists, and feet, but RA can affect any joint.

One of the defining features of rheumatoid arthritis is its systemic nature. Unlike osteoarthritis, which primarily affects individual joints, RA can impact multiple joints symmetrically (for example, wrists or knees) and cause complications beyond the joints. The ongoing inflammation associated with RA can affect other organs and tissues, leading to a range of systemic symptoms. Common systemic effects of RA include fatigue, general malaise, and anaemia. In more severe cases, rheumatoid arthritis can lead to complications such as lung inflammation (rheumatoid lung), heart problems (including an increased risk of cardiovascular disease), and eye conditions like dry eyes or inflammation (scleritis or uveitis). These widespread effects underscore the importance of recognising and managing RA as a whole-body condition, not just a joint disorder.

-

Diagnosis and Treatment

Diagnosing rheumatoid arthritis involves a combination of clinical evaluation, laboratory tests, and imaging studies. Healthcare providers typically begin by assessing the patient’s symptoms, particularly the pattern and duration of joint pain and stiffness. Given that RA can be challenging to diagnose in its early stages, especially since its symptoms can mimic other conditions, specific blood tests are crucial in confirming the diagnosis. These tests often include checking for rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibodies commonly found in individuals with RA. Elevated levels of inflammatory markers, such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP), can also indicate the presence of an inflammatory process in the body.

Imaging tests, such as X-rays, ultrasound, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), are often used to assess the extent of joint damage and monitor the disease’s progression. These imaging techniques can reveal characteristic joint changes, such as bone erosion and joint space narrowing, indicative of rheumatoid arthritis.

Treatment for rheumatoid arthritis aims to control the autoimmune response, reduce inflammation, relieve symptoms, and prevent joint and organ damage. The cornerstone of RA treatment is the use of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), which work to slow down the progression of the disease and protect the joints from further damage. Methotrexate is one of the most commonly prescribed DMARDs, often used as a first-line treatment; for patients who do not respond adequately to DMARDs, biological agents targeting specific immune system components may be used. These biologics, such as tumour necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, have revolutionised the treatment of RA, providing significant relief for many patients.

In addition to DMARDs and biologics, corticosteroids may be used to reduce inflammation and rapidly control acute flare-ups of the disease. However, due to potential side effects, long-term use of corticosteroids is generally avoided. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can also be used to manage pain and reduce inflammation but do not alter the course of the disease.

Lifestyle modifications play a critical role in managing rheumatoid arthritis. Patients are encouraged to engage in regular physical activity tailored to their abilities, maintain a healthy weight, and avoid smoking, as these factors can influence disease activity and overall health. Early diagnosis and aggressive treatment are crucial to managing RA effectively, preventing joint damage, and maintaining a good quality of life.

Differences Between Osteoarthritis and Rheumatoid Arthritis

-

Causes

Osteoarthritis (OA) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) are fundamentally different in their underlying causes. Osteoarthritis is primarily a degenerative condition that results from physical wear and tear on the joints over time. It occurs when the cartilage that cushions the ends of bones in a joint gradually deteriorates, leading to bones rubbing against each other. This mechanical breakdown is often due to ageing, repetitive joint use, and previous injuries. Factors such as obesity, which places additional stress on weight-bearing joints, and genetic predisposition can further increase the risk of developing OA.

In contrast, rheumatoid arthritis is an autoimmune disease, meaning that it is caused by the body’s immune system mistakenly attacking its tissues, specifically the synovium, the lining of the joints. This immune response leads to inflammation, resulting in joint damage and affecting other parts of the body. The exact triggers for this autoimmune response are not fully understood. Still, it is believed to involve a combination of genetic factors, hormonal influences, and environmental triggers, such as infections or smoking. Unlike OA, a consequence of mechanical characteristics, RA is driven by an aberrant immune response.

-

Symptoms and Affected Joints

The symptoms of osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis differ in nature and the patterns they present within the body. Osteoarthritis is characterised by joint pain that worsens with physical activity and eases with rest. The pain is often accompanied by stiffness, mainly after periods of inactivity, but it tends to improve once the joint is warmed up with movement. OA usually affects weight-bearing joints such as the knees, hips, and spine, and it often progresses asymmetrically, meaning one side of the body may be more affected than the other. The joints in the hands, particularly those at the base of the thumb, can also be involved, but the condition generally remains localised to the joints under the most stress.

Rheumatoid arthritis, on the other hand, presents with pain that is often worse after periods of inactivity, especially in the morning or after long periods of rest, a phenomenon known as morning stiffness. This stiffness can last for an hour or more and may be accompanied by swelling, warmth, and tenderness in the affected joints. Unlike OA, which typically affects individual joints, RA usually affects multiple joints symmetrically, meaning the same joints on both sides of the body are involved. Commonly affected joints include the small joints of the hands, wrists, and feet, but larger joints like the knees and elbows can also be involved. Additionally, RA’s systemic nature means it can cause symptoms beyond the joints, such as fatigue, fever, and loss of appetite.

-

Progression and Impact on the Body

Osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis also differ in how they progress and impact the body. Osteoarthritis is a slow, progressive disease that primarily affects the joints. Over time, as the cartilage continues to wear down, the joint space narrows, and the bones may develop spurs (osteophytes) or become misshapen. While the progression of OA can lead to significant joint pain and disability, it is generally limited to the affected joints and does not involve other systems of the body.

Rheumatoid arthritis, in contrast, can have a much more rapid onset, with symptoms developing over weeks to months. Because RA is an autoimmune disease, its effects are not confined to the joints. The chronic inflammation associated with RA can lead to significant joint damage, deformities, and loss of function, often within the first few years if not adequately treated. Moreover, RA’s systemic nature means it can affect other organs, including the heart, lungs, and eyes, leading to complications such as cardiovascular disease, lung inflammation, and eye problems. This systemic involvement underscores the seriousness of RA and the need for early and aggressive treatment.

-

Treatment Approaches

The treatment strategies for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis reflect their differences in causes and progression. Osteoarthritis treatment primarily focuses on managing symptoms and maintaining joint function. This typically involves pain management, physical therapy, and lifestyle modifications such as weight loss and regular exercise to reduce joint stress. Over-the-counter pain relievers like paracetamol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are commonly used to alleviate pain and reduce inflammation. In more severe cases, joint injections or surgical interventions, such as joint replacement, may be necessary to restore function.

Rheumatoid arthritis requires a more aggressive treatment approach aimed at controlling the immune response and preventing further joint damage. The cornerstone of RA treatment is the use of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), which slow the disease’s progression and reduce inflammation. Biologic agents, a newer class of DMARDs, target specific immune system components and are often used when traditional DMARDs are ineffective. Corticosteroids may be used to control acute flare-ups, while NSAIDs are employed for pain relief. Lifestyle changes, including exercise and smoking cessation, are also recommended to help manage RA and reduce the risk of complications.

| Aspect | Osteoarthritis (OA) | Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) |

|---|---|---|

| Causes | Primarily caused by mechanical wear and tear on the joints. Risk factors include age, obesity, previous joint injuries, and genetics. | An autoimmune disease where the immune system mistakenly attacks the joint lining. Influenced by genetic predisposition, environmental factors, and hormonal influences. |

| Symptoms | Joint pain that worsens with activity and improves with rest. Often accompanied by stiffness and reduced flexibility. | Joint pain, swelling, and stiffness, particularly worse after periods of inactivity (e.g., morning stiffness). It is also associated with fatigue and systemic symptoms. |

| Affected Joints | Typically affects weight-bearing joints such as the knees, hips, and spine. It usually affects joints asymmetrically. | Affects multiple joints symmetrically, commonly in the hands, wrists, and feet. It can also involve larger joints. |

| Progression | Progresses slowly over time, primarily affecting the joints. Limited to the joints with no systemic involvement. | Can have a rapid onset with systemic involvement, potentially affecting other organs such as the heart, lungs, and eyes. |

| Treatment Approaches | Focuses on managing pain and maintaining joint function. Includes pain relievers, physical therapy, lifestyle changes, and, in severe cases, surgery. | Requires more aggressive treatment to control the immune response and prevent joint damage. Includes DMARDs, biologics, corticosteroids, and lifestyle modifications. |

Living with Osteoarthritis and Rheumatoid Arthritis

Living with osteoarthritis (OA) or rheumatoid arthritis (RA) presents daily challenges, but with the right strategies, individuals can manage their symptoms effectively and maintain a good quality of life. One of the most important aspects of managing both conditions is regular exercise. For those with OA and RA, staying active helps maintain joint flexibility, strengthens the muscles around the joints, and reduces pain. Low-impact activities like swimming, walking, and cycling are particularly beneficial, as they put less strain on the joints while providing essential cardiovascular and muscular benefits.

Weight management is another crucial factor in managing arthritis. Excess weight places additional stress on weight-bearing joints, particularly in the knees and hips, exacerbating the symptoms of OA and potentially worsening the progression of RA. A healthy diet, rich in anti-inflammatory foods such as fruits, vegetables, and omega-3 fatty acids, can help control inflammation, support overall health, and make weight management easier.

In addition to lifestyle changes, assistive devices can significantly impact daily life for those with arthritis. Canes, walkers, and specialised footwear can help reduce pain and improve mobility by providing additional support and reducing the load on affected joints. Physical therapy is also highly beneficial for OA and RA patients, as it offers tailored exercises that improve joint function and flexibility, reduce pain and enhance overall mobility.

-

Emotional and Psychological Impact

The emotional and psychological impact of living with a chronic condition like osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis cannot be overstated. The persistent pain, mobility limitations, and the knowledge that these conditions are lifelong can lead to feelings of frustration, anxiety, and depression. Individuals with OA and RA need to acknowledge these emotional challenges and seek support when needed.

Support from healthcare providers, such as rheumatologists and physiotherapists, is essential in managing the physical aspects of the disease, but emotional support is equally important. Engaging with support groups, whether in person or online, can provide a sense of community and understanding that is invaluable in coping with the emotional toll of arthritis. These groups offer a space to share experiences, learn from others facing similar challenges, and gain emotional support.

Mental health professionals, such as counsellors or psychologists, can also play a crucial role in helping individuals manage the stress, anxiety, or depression that may accompany chronic illness. Techniques such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) can be particularly effective in helping individuals develop coping strategies, reframe negative thought patterns, and improve their overall mental well-being.

-

Ongoing Care and Monitoring

Ongoing care and regular monitoring are vital to managing osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Both conditions can progress over time, and regular check-ups with a healthcare provider are essential to monitor the disease’s progression, assess the effectiveness of treatment plans, and make necessary adjustments. For individuals with RA, early and aggressive treatment is vital in preventing joint damage and systemic complications, making regular consultations with a rheumatologist particularly important.

Staying informed about new treatments and management strategies is also crucial for those with arthritis. Medical research is continually advancing, and new therapies, medications, and lifestyle recommendations are emerging that can significantly improve quality of life. Patients should feel empowered to discuss these options with their healthcare providers and explore whether new treatments might suit their condition.

Ultimately, managing osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis requires a comprehensive, proactive approach that includes physical care and attention to emotional well-being. By maintaining a healthy lifestyle, seeking support, and staying engaged with ongoing care, individuals with OA and RA can effectively manage their symptoms, prevent complications, and lead fulfilling lives despite the challenges posed by these conditions.

Vale Health Clinic

At Vale Health Clinic, we offer a comprehensive range of treatment options tailored to manage arthritis and osteoarthritis effectively:

- Chiropractic Care: Our skilled chiropractors provide treatments to alleviate pain and enhance joint function, which can be particularly beneficial for arthritis sufferers.

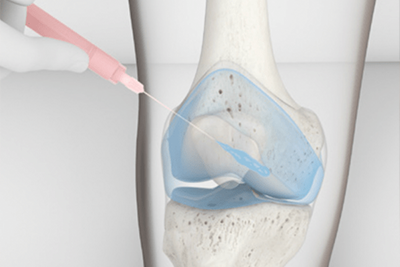

- Hyaluronic Acid Injections: We utilise advanced hyaluronic acid injections, such as Durolane, to restore joint lubrication and cushioning, thereby reducing pain and improving mobility.

- Arthrosamid® Injections: This innovative treatment offers long-lasting pain relief for knee osteoarthritis through a single injection, promoting tissue repair and accelerated healing.

- Cingal® Injections: Combining hyaluronic acid with a steroid, Cingal® provides immediate and sustained relief from osteoarthritis pain, enhancing joint function and delaying surgical interventions.

- Ostenil® Plus Injections: These injections help restore the balance of hyaluronic acid in the joint, significantly reducing pain and stiffness associated with osteoarthritis.

Our clinic is dedicated to offering personalised treatment plans to effectively manage arthritis and osteoarthritis, aiming to improve your quality of life.

Related Articles:

- Osteoarthritis Management and Self Care

- What Are Hyaluronic Acid Injections?

- Managing Osteoarthritis (OA) Knee Pain

- Myths about Arthritis

- Diet and Nutrition For Arthritis